There is an old saying that goes, “The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.” It’s a cliche at this point and has been dulled so that we no longer feel the sting of the truth it’s pointing to. However, once in a while, fiction, in its great quest to mirror life, gives us a sharper look into simple truths we take for granted.

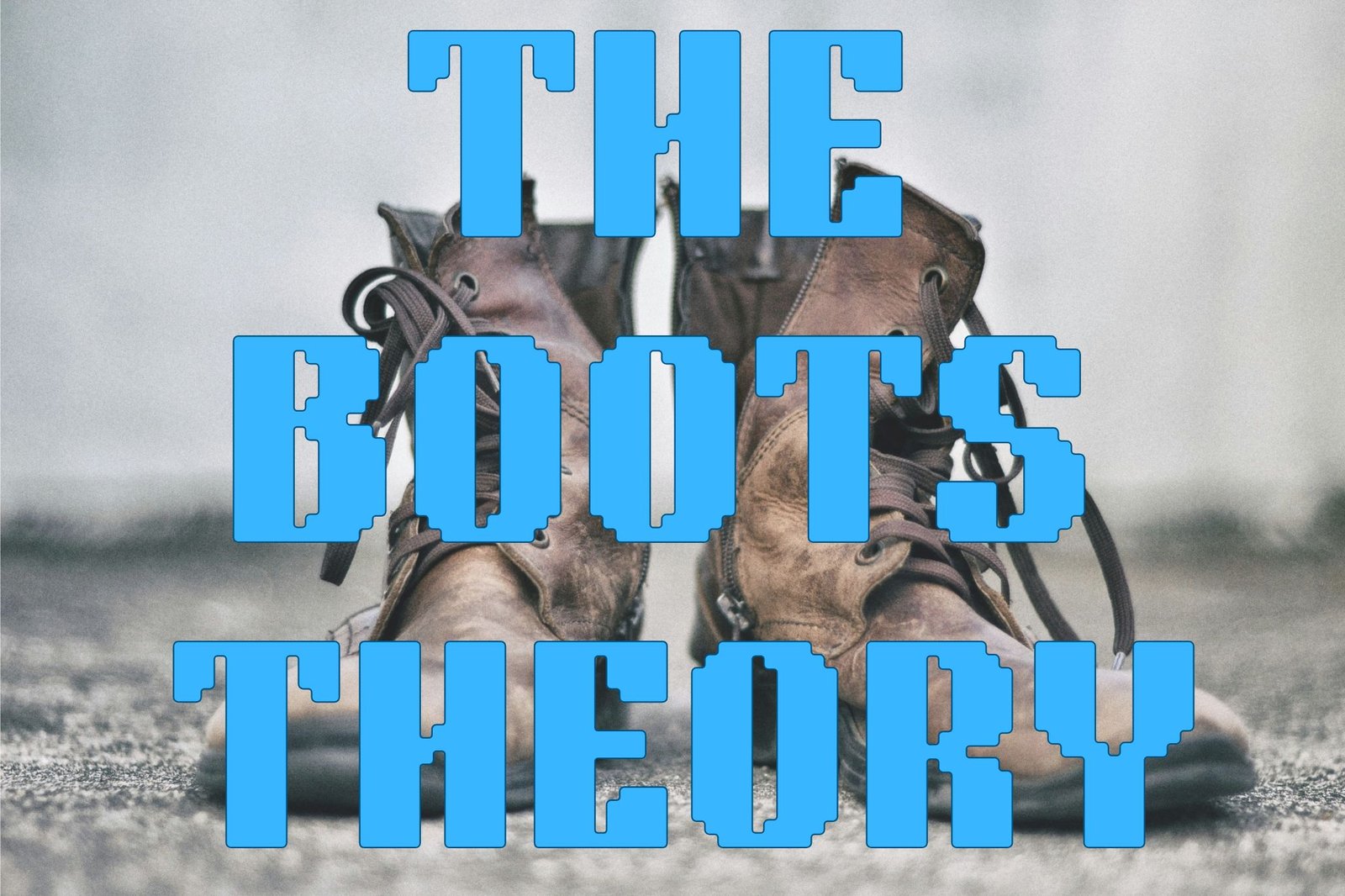

In 1993, fantasy author Terry Pratchett introduced one of the most elegant economic theories ever in a book about dwarfs, trolls, and an alcoholic city watchman.

It’s called the Boots Theory, and once you understand it, you can’t unsee it in the real world.

Samuel Vimes and the $10 Boots

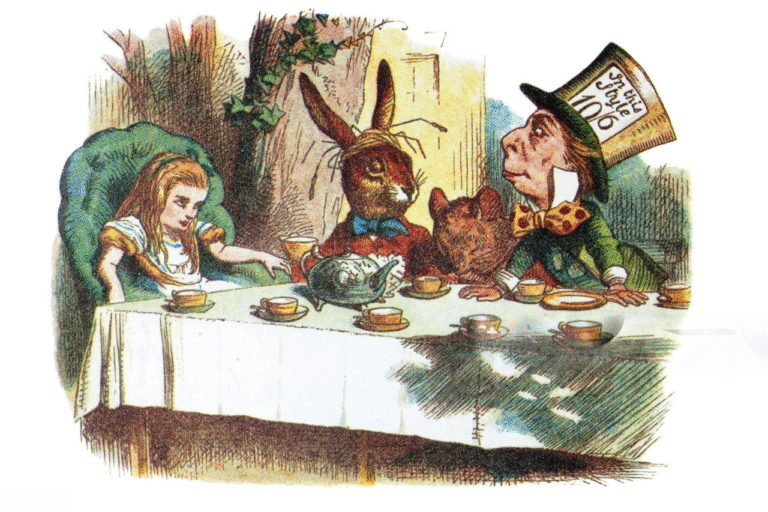

In Men at Arms, one of the books in Pratchett’s Discworld series, Captain Samuel Vimes, a deeply cynical but deeply principled watchman born into poverty, reflects on the economics of boots:

“The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money.

Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of OK for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars.

Those were the kind of boots Vimes always bought, and wore until the soles were so thin that he could tell where he was in Ankh-Morpork on a foggy night by the feel of the cobbles.”

While Pratchett is no longer with us, this theory was re-shared on twitter by his estate in 2022, which is timely given what the world is coming to.

It’s not just great writing; it’s microeconomic truth. This simple anecdote makes one thing very clear: BEING POOR IS EXPENSIVE!

Poverty Has An Interest Rate

Vimes was describing a very real phenomenon; the hidden cost of poverty, the inability to invest in durability or the massive discounts of buying in bulk or directly from manufacturers through special or funded access.

The poor are forced to buy disposability, whether it is in the form of boots, cheap appliances, housing, or food and thus end up paying more over time for lower quality. Do not forget, there is always a markup for buying things in singular portions or smaller units and volumes.

Meanwhile, the wealthy can afford the initial capital required to save money, time, and even health in the long run. Their ‘$300 boots’ in this scenario only need to be bought once. You can buy $30 knock-offs ten times and still end up with blisters and debt.

Economists call this “regressive cost burden” or if you want a less boring term, the “poverty premium.”

It’s the idea that the less you have, the more things cost you in both tangible and intangible ways. Whether it’s banking fees, higher-interest loans, pay-as-you-go phones, or a lack of access to preventative healthcare, the system punishes you for not having money in compounding ways.

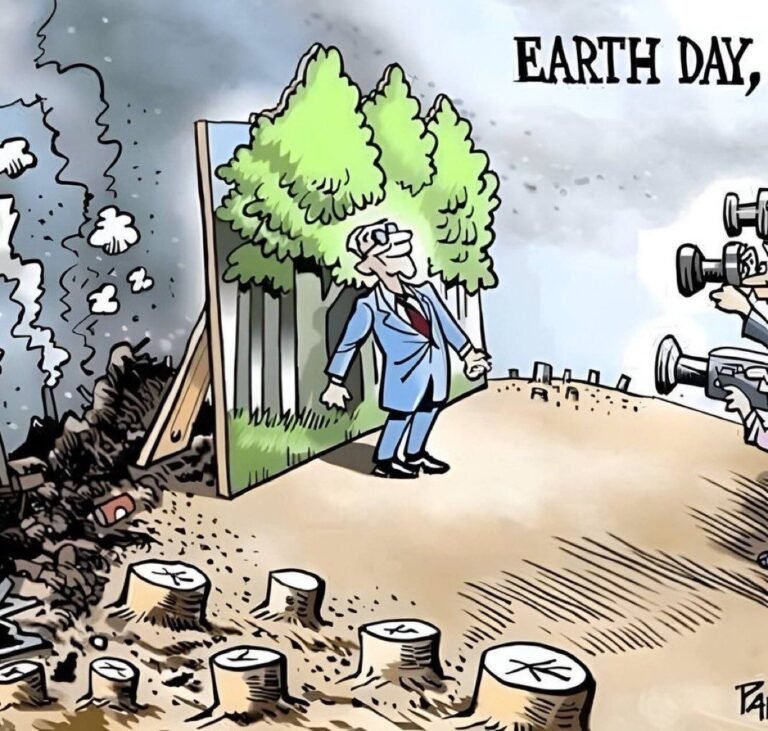

Someone Created A Real-World Boots Index

Spurred on by the very real phenomenon this idea presents, a food writer and poverty campaigner named Jack Monroe created the Vimes Boots Index. It is named after Pratchett’s fictional captain and tracks how inflation disproportionately affects the cheapest, most essential goods.

Standard inflation statistics are too broad and track average price increases, which do not reflect the skyrocketing prices you have probably experienced on stuff like rice, flour, cooking oil, and basic household items. Premium goods remained relatively stable.

The poor, once again, were shown to be paying more for less.

This move even prompted the UK’s Office for National Statistics to adjust its methods after Monroe’s viral thread.

Life, in this case, imitated the powerful, revealing truths of art.

Wealth Buys Efficiency

The benefits of wealth go beyond consumer goods. Think about time as another commodity. As a poor person, you’ll spend more time on public transportation, in queues for government services, managing chaos because you can’t afford to have a bad few days, etc.

You do not get sick leave, you can’t outsource your work, and you must work hours that destroy any chance to work on something else, like an investment. Your life is optimized for survival, not progress.

Wealth gets you insulation: better lawyers, phone calls instead of queues, Wi-Fi that doesn’t blink out in the middle of an important call, indoor climate regulation, personal vehicles to go wherever they please, and more.

It’s not just about the stuff, it’s about the systems.

Why Don’t You Just Live Within Your Means?

Some weirdos will look at your hard situation and tell you to live within your means and save. First of all, save what? This myth that the poor just need to budget better is used to beat unfortunate members of society over the head.

You get told that you can “pull yourself up by your bootstraps.”

It’s kind of a funny and strangely weird thing to say, given that you CAN’T ACTUALLY DO THAT if you tried. Go ahead, try it and see. Grab your favourite boots, wear them, and try to pull yourself up without jumping. It’s a cruel thing to say, is what I am trying to tell you here.

Pratchett, through Vimes, understood that poverty is not a lack of character; it’s the consequences of inefficiency and systems that maintain insane levels of wealth inequality. Efficiency can be yours, but it comes with a high upfront cost, like those $300 boots. You can’t spend money that’s already been stolen from you, but that’s not what this is about.

What To Do

The first step is understanding the theory and what it means. The second step is pushing back against systems that punish people for being poor. That means:

- Regulations against predatory companies and practices

- Increasing access to affordable, sustainable, and durable goods and services.

- Supporting policies like universal healthcare, public transportation, subsidized childcare, and other social programs aimed at addressing the causes of poverty.

- Critically listening to people who live this reality instead of ‘giving advice’ from the outside.

We need to do a lot more, including changing how we talk about poverty. It’s not a moral failing or budgeting error. It’s a systemic condition that, when treated as a symptom of individual bad choices, only gets worse.

Terry Pratchett was not an economist. He was a humanist with a keyboard who, in a few words, talking about a pair of boots, captured something the World Bank takes an entire library to model.

Next time you feel someone needs to know this, feel free to direct them to this article. Thanks.